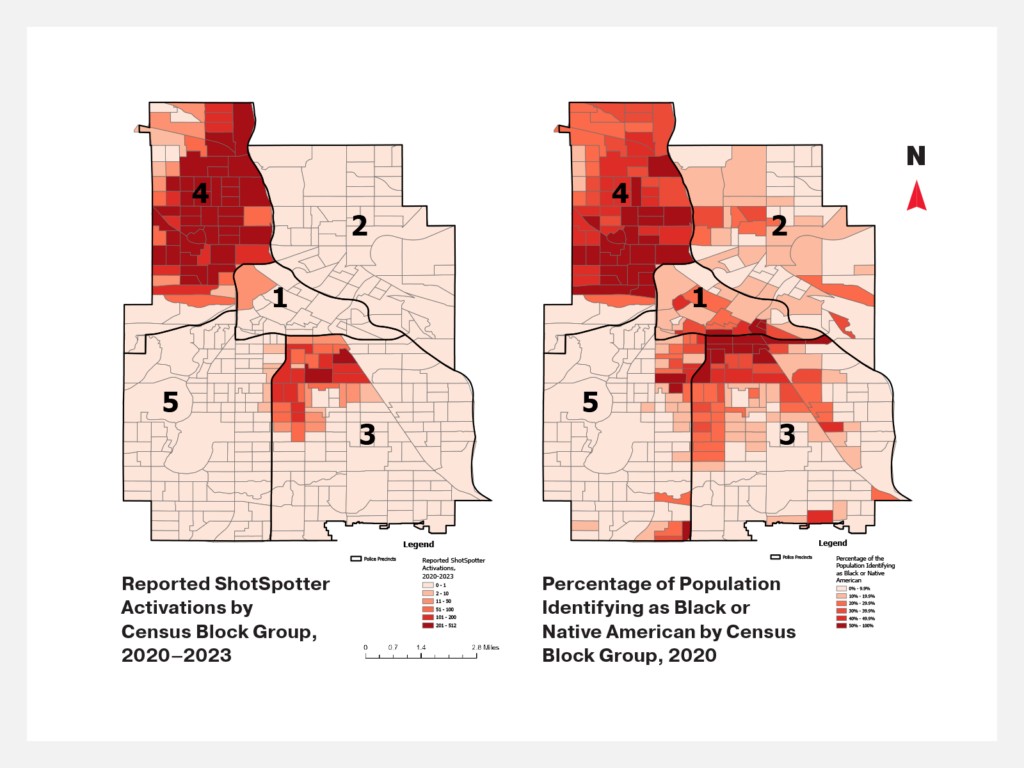

Analyzing public data from 2020 to 2023, Lindenfelser’s study reveals a disproportionate impact on Black and Native American communities in Minneapolis, emphasizing the technology’s contribution to over-policing without clear benefits in safety or gun violence reduction.

Despite its touted capabilities, ShotSpotter’s implementation has proven a negative impact on communities of color. ShotSpotter’s use contributes to over-policing in these neighborhoods,1 leading to unwarranted stops and searches based on system-generated alerts. Despite its widespread adoption, ShotSpotter has yet to demonstrate a significant effect on reducing firearm-related homicides or improving safety.

What is ShotSpotter?

Developed by SoundThinking, Inc., ShotSpotter is a technology that claims to detect gunshots using a combination of microphones, unproven software, and human review.

However, ShotSpotter is not error-proof and often makes mistakes. ShotSpotter fails to detect all actual instances of gunfire.2 Worse still, ShotSpotter confuses fireworks, vehicle backfires, and other loud sounds for gunfire,3 creating alerts that often lead to unnecessary police responses. Innocent bystanders near a ShotSpotter activation may be subject to stops and searches based on the alert alone. Rather than making communities safer, ShotSpotter technology contributes to over-policing of Black and Brown communities.4

Black and Native Americans in Minneapolis are 3.3x more likely to live in areas with ShotSpotter coverage than white people.

The neighborhoods in Minneapolis impacted by ShotSpotter were determined by analyzing public data on ShotSpotter activations.5 Based on where these activations occur, it is clear that ShotSpotter is placed in neighborhoods with higher percentages of people identifying as Black or Native American.

The financial and social costs

Since 2007,6 Minneapolis has invested over $2.2 million7 in ShotSpotter, with costs continuing to rise. Minneapolis spent $48,840 per year on ShotSpotter in 2012, which rose to $111,667 per year in 2019.8 This expenditure comes at the expense of alternative, community-led safety initiatives.

At least 16 other cities have canceled their ShotSpotter contracts, most recently Chicago.9 At least 19 other cities have considered and rejected a ShotSpotter contract, including St. Paul.10

A call to collaborate with impacted communities, rather than rely on bad tech

Black and Native communities in Minneapolis already face over-policing and discriminatory violence.11 Placing ShotSpotter in these communities increases interactions between civilians and police.

Instead of paying millions for an unreliable technology, Minneapolis could spend the money better on programs that improve gunfire reporting in collaboration with the communities most impacted by it.

Contact your Reps to #CancelShotSpotter

Tell them that ShotSpotter doesn’t stop shootings, wastes money, and doesn’t make us safer. We need real solutions for gun violence, not expensive contracts. These contracts can be terminated anytime, so let’s cancel them now.

For more information, visit our website. Please email us at [email protected] to collaborate with our campaign.

Endnotes

- Benjamin Goodman, Shotspotter – The New Tool to Degrade What Is Left of the Fourth Amendment, 54 UIC L. Rev. 797, 820–21 (2021) (“The implementation of ShotSpotter can lead to over policing in specific neighborhoods. . . . they often end up being neighborhoods inhabited largely by Black and Brown people.” (footnotes omitted)); Harvey Gee, “Bang!”: Shotspotter Gunshot Detection Technology, Predictive Policing, and Measuring Terry’s Reach, 55 U. Mich. J. L. Reform 767, 769 (2022) (“In the past few years, many young, Black men . . . have been arrested or harassed because they have had the misfortune of being in an area where gunshots were allegedly heard. This injustice is the result of ShotSpotter technology. . . .”); see Dhruv Mehrotra and Joey Scott, Here Are the Secret Locations of ShotSpotter Gunfire Sensors, WIRED (Feb. 22, 2024), https://www.wired.com/story/shotspotter-secret-sensor-locations-leak/ (finding that “in aggregate, nearly 70 percent of people who live in a neighborhood with at least one SoundThinking sensor identified in the ACS data as either Black or Latine” and including a quote from a senior SoundThinking official that he was “willing to accept that our findings are true”); End Police Surveillance, ShotSpotter creates thousands of unfounded police deployments, fuels unconstitutional stop-and-frisk, and can lead to false arrests, Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center, https://endpolicesurveillance.com/ (finding that ShotSpotter “creates thousands of unfounded police deployments, fuels unconstitutional stop-and-frisk, and can lead to false arrests.”). ↩︎

- Jim Daley, Max Blaisdell, In Chicago, ShotSpotter Failed to Detect Hundreds of Shootings, The Appeal (Jan. 29, 2024), https://theappeal.org/chicago-shotspotter-missed-shootings-brandon-johnson/ (finding that “[i]n December 2022, ShotSpotter sensors in Chicago failed to detect a shooting in which 55 rounds were fired and two men were wounded” and “[b]etween Jan. 1 and Dec. 18, 2023, Chicago police emailed ShotSpotter 575 times to report gunfire the department said sensors missed.”). ↩︎

- Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center, ShotSpotter Generated Over 40,000 Dead-End Police Deployments in Chicago in 21 Months, According to New Study (May 3, 2021), https://www.macarthurjustice.org/shotspotter-generated-over-40000-dead-end-police-deployments-in-chicago-in-21-months-according-to-new-study/. ↩︎

- Goodman, Gee, Mehrotra and Scott, and MacArthur Justice Center, supra note 1. ↩︎

- Steven Manson, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, Katherine Knowles, Tracy Kugler, Finn Roberts, and Steven Ruggles, IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 18.0 US_blck_grp_2010.shp, IPUMS (2023), https://www.nhgis.org/; Id., ts_geog2010_blck_grp; MapIT Minneapolis, Minneapolis Police Precincts, Minneapolis GIS (Jun. 23, 2022), https://opendata.minneapolismn.gov/datasets/cityoflakes::minneapolis-police-precincts/about; MapIT Minneapolis, Shots Fired, Minneapolis GIS (Dec. 28, 2023), https://www.minneapolismn.gov/resident-services/public-safety/police-public-safety/crime-maps-dashboards/shots-fired-map/. ↩︎

- Electronic Frontier Foundation, Atlas of Surveillance: Minneapolis Police Department: Gunshot Detection, https://atlasofsurveillance.org/a/aos006770-minneapolis-police-department-gunshot-detection. ↩︎

- Minneapolis, Minn. Council Action No. 2019A-0702 (2019). ↩︎

- Contract for Professional Services No. C-35511, Fifth Amendment to City of Minneapolis Contract Number C-35511, https://www.muckrock.com/foi/minneapolis-1607/shotspotter-contract-minneapolis-police-department-131860/#file-1041541 ↩︎

- Campaign Zero, Is ShotSpotter Near You?, CancelShotSpotter.Com, https://cancelshotspotter.com/#research; Mayor’s Press Office, City Of Chicago Statement On ShotSpotter Contract, City of Chicago (Feb. 13, 2024), https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/mayor/press_room/press_releases/2024/january/city-of-chicago-statement-on-shotspotter-contract.html. ↩︎

- Id ↩︎

- United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and United States Attorney’s Office District of Minnesota Civil Division, Investigation of the City of Minneapolis and the Minneapolis Police Department 31 (2023); Michelle S. Phelps, et al., Over-Policed and Under-Protected: Public Safety in North Minneapolis, CURA Reporter (Nov. 17, 2020), https://www.cura.umn.edu/research/over-policed-and-under-protected-public-safety-north-minneapolis. ↩︎

- Alexander Lindenfelser would like to thank/acknowledge Mattie Gisselbeck and Diego Osorio of the University of Minnesota GIS Lab and Alejandrea Brown of the Minnesota Journal of Law and Inequality for their help on this project. The authors acknowledge U-Spatial at the University of Minnesota for providing resources that contributed to this research. URL: uspatial.umn.edu.